Photo credit: Alexis Wuillaume

We chat to Diggin in the Carts’ Nick Dwyer — documentarian, radio and TV presenter, promoter, DJ, tastemaker, and probably the world’s foremost expert on classic Japanese video game chiptune.

By Thomas Quillfeldt

Look. The major music streaming services — Spotify, Apple Music, etc. — might boast of 50 million music tracks; and YouTube might well be the largest repository of music in human history. But a lot of music either hasn’t made its way into the online realm, and you can be damn sure that no one has the forbearance to listen to the vast majority of it even if it were.

When it comes to classic video game music though, there exists one such person with the forbearance to listen to everything and highlight the gems — so the rest of us don’t have to spend the time.

Whilst the game music fandom (us included!) digests yet another critique, cover, or concert of the beloved music of Final Fantasy, Journey, or Skyrim, Nick Dwyer and his regular collaborators — under the brand Diggin in the Carts — continue to shine a light on less well-known game music. Through documentaries, radio programmes, compilations, and live tours, Diggin in the Carts is about highlighting tracks predominantly from the golden age of video game chiptune (i.e. music voiced by a console or computer sound chip c. 1983-1995) that may be in danger of fading into the past.

Take our word for it: the New Zealand native is one of the most interesting people in the world of music, let alone video game music. Part presenter-producer across radio, TV and online video; part tastemaker-DJ; part live promoter; and part cultural historian and documentarian, Dwyer’s established himself as a true maven of ‘80s and ‘90s VGM. There’s an educational angle to his work: not just to catalogue and celebrate, but also to draw clear connections between historical chiptune and contemporary electronic music.

He talked us through his history with game music, how the various Diggin’ projects came to be, and how Japanese composers of the chiptune era feel about the lionisation of their older work by fans today.

(With Nick’s expert input, we’ll take a closer look at the relationship between electronic music and video game music in the mid-’90s in a future article — keep an eye on our channels for that one.)

Origins of a cart digger

Photo credit: Alexis Wuillaume

You can infer from the way Nick Dwyer talks about his childhood — in infectiously enthusiastic tones laced with genuine humility — that he must have developed impeccable music taste in the womb (or at least by early school age.)

He attributes this connoisseurship to his older brother and sister who ensured that he heard great music from a mind-bogglingly young age: a heady brew of Madness, The Specials, Thompson Twins, The Cure, and the catalogue of famed New Zealand record label Flying Nun.

As he was developing his (tiny) ear for all sorts of music, along came computer and video games with killer soundtracks. The Last Ninja (1987) on the Commodore 64 didn’t just spark a love of VGM in seven-year-old Nick — it was effectively his introduction to the possibilities of electronic music as well. “That soundtrack floored me. I would use my brother's cassette deck to record and listen back to it. It was so dark and unlike anything I'd ever heard.”

For Dwyer, Ben Daglish and Anthony Lees’ score for The Last Ninja stood in contrast to his siblings’ band records, and it also heralded a step up from mid-’80s VGM (he pointedly rejects the use of the phrase ‘bleeps and bloops’ to disparage this era.) “Before I heard The Last Ninja I wasn’t taking much notice of game music. In retrospect, [he may have been put off because] a lot of the English game composers of the time were ripping off major tunes, for instance Zaxxon borrowing from Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet; or the theme tune to International Karate taking elements of the film score for Merry Christmas. Mr. Lawrence.”

Sadly, both Ben Daglish (obit.) and Anthony Lees (obit.) have passed away in recent years, although Dwyer did get the chance to interview the former for the third series of the Diggin’ radio show.

Dwyer’s brother later visited Japan and sent a Super Famicom (the Japanese equivalent of the SNES) back home. “I was thrilled. I had some of the usual games — Super Mario and Final Fight — and a terrible game called Battle Blaze.

“Later on, some Japanese homestays brought with them Final Fantasy V and Dragon Quest V — the only trouble was that I couldn't speak Japanese! I bought a dictionary and taught myself how to read and write [Japanese writing character sets] Hiragana and Katakana, enabling me to beat those games and also Final Fantasy VI. I have a deep personal connection to those JRPGs and their soundtracks.” To seal his love of games and game music, getting to play Chrono Trigger — in English this time — drew him in “hook, line, and sinker.”

Around 14-15 years old, Dwyer started working at a radio station playing alternative and underground music, and got “caught up in the buzz of rave culture” whilst going to warehouse parties and listening to jungle. He went on to DJ, promote parties, and buy in the hottest records for a legendary drum’n’bass music store. As a music video presenter, he went on to introduce cutting edge new music on “New Zealand’s version of MTV.”

We’ll explore in more detail how electronic music makers were influenced by video game sounds in a forthcoming Laced With Wax piece; suffice to say that in the early-to-mid-’90s, Dwyer was encountering plenty of crossover between VGM and dance music (before the oft-cited WipEout hit the scene.) He remembers Jo’s “R-Type” as a standout example of such crossover:

Making treks

By his mid-20s, Dwyer had spent 10 years as a music broadcaster in New Zealand, and it was time to spread his wings.

National Geographic hired him to front globetrotting music/travel show Making Tracks, during the course of which he ‘exchanged the sounds of New Zealand for the sounds of the world.’ He got to visit some of the world’s most creatively teeming local music scenes across Africa, the Caribbean, the Middle East, South America, and more.

In filming the Tokyo episode of Making Tracks, Dwyer’s love of VGM and his professional life as a music broadcaster converged. “I remembered how much of an impact game music had on me when I was a kid, and I wanted to find out more from the people who made that music, so we set up interviews with Hirokazu ‘Hip’ Tanaka (Metroid, Tetris) and Yoko Shimomura (Street Fighter II, Kingdom Hearts) for the show. They were wonderful to speak to, and that’s where the first seeds of the Diggin in the Carts documentary series were planted.”

Diggin' for gold

Here’s a quick survey of what the overarching Diggin in the Carts project actually consists of (as of May 2019):

- 2014 – A six-part online documentary series featuring interviews with Japanese composers and contemporary electronic music artists

- 2016-2018 – Three series (1, 2, & 3) of a radio show featuring VGM playlists and interviewees

- 2017 – A compilation of chiptune classics released by Hyperdub

- 2017-2018 – A world tour of two live shows: Yuzo Koshiro and Motohiro Kawashima performing music from Streets of Rage; and a VGM-inspired set by Kode9 set to visuals by Kōji Morimoto (Akira)

- 2019 – A remix EP by Kode9

Recalls Dwyer: “I’d been travelling to Japan once or twice a year from 2008 onwards. I started to think about the fact that 8-bit sounds had been sampled a lot in electronic music — had been given their due — as had all those epic JRPG soundtracks [Final Fantasy, etc.]” He spotted a gap: “Since I had a Super Famicom, I knew how many games were never released in the West. I decided I was going to get my hands on all of those super-rare 16-bit JRPGs, I was going to sample them, and it was going to be great.

“Every time I went to Japan I would go digging in shops like Super Potato and I started finding all this killer music. The more that I found, the more I wanted to find out about these composers — but nothing existed. I thought: ‘someone needs to make a documentary series about these people… Hang on, I make TV docs. Why don’t I do it?!’”

In a Wild City interview, Dwyer says that it was as he was looking out of a 30th floor hotel window at the nighttime Tokyo skyline with “Waltz of Meditation Part 2” by Hitoshi Sakimoto from Magical Chase blaring that he made up his mind to make Diggin in the Carts a reality.

At the time, Red Bull had been pumping a lot of marketing money into its sports and culture initiatives, including the Red Bull Music Academy — an educational gathering for up and coming musicians, now sadly coming to an end in 2019. It just so happened that the 2014 RBMA was located in Tokyo, which was the catalyst that Dwyer needed to successfully pitch the Red Bull team for funding to make the documentary.

He and his close friend, video producer Tu Neill, set about making the six-part series, which intercuts interviews with Japanese chiptune composers, developers, journalists and experts with cutting-edge contemporary music artists who have been influenced by VGM.

Dwyer is clearly not a person who does things by half: “Each time I do a new series of the radio show, or in preparation for the documentary, I listen through everything. Every game. Every song. It takes a long time.

“For this whole project, I've listened to something like 250,000 tracks, maybe 300k, across 8-bit and 16-bit consoles, as well as Japanese PC systems including the MSX and PC8801.” He jokes: “A lot of it is awful! Horrible! But it's that 5% of gold that shines so brightly. There's a thrill in that process of discovery.”

He draws a direct line from his voracious childhood listening habits, via his work as a radio DJ and TV presenter, to the various Diggin’ projects. “I've been on this non-stop mission to discover, to learn as much about the music of the world as possible. Music is a way to learn about history and societies around the world.

“Delving the depths of Japanese game music, and subsequently into British VGM, is no different to me exploring South African Kwaito, or Nigerian High Life, or calypso, or soca. It’s just another treasure trove of music I’ve found a reason to explore. I love that thrill of coming across a new era, or genre, or subgenre, and thoroughly going through it.”

Championing chiptune

Although the focus has been relaxed over the course of the radio shows, the initial scope of Diggin in the Carts was limited to Japanese chiptune up to 1995 (i.e. the end of the 16-bit era.)

Dwyer admits: “When [co-producer] Tu and I made the documentary, I kind of believed that after Redbook audio (i.e. CD-quality audio streaming from the disc) was introduced, video game music lost its uniqueness. I felt that those sound chips were [essentially musical] instruments with their own individual charm and personality. I loved that era, and felt that those composers were pushing the boundaries of what was possible.

“They were trying to take musical ideas and cues from outside the world of video games — e.g. orchestral sounds or jazz— and trying to emulate them, but not quite getting there. That was the charm. When CD audio came in, composers started to make ‘real’ jazz or ‘real’ rock and game music lost its charm, for me.”

Dwyer’s and his collaborators’ mission was (and still is) to bring this music and these composers to a new audience, whilst also getting the perspective of other musicians from around the world that had been inspired by VGM. He had met music artists such Flying Lotus and Dizzie Rascal over the years and chatted to them about the work of Nobuo Uematsu and co. It was important to feature contemporary musicians in the documentary to demonstrate to people outside of the video games bubble how influential this music has been.

Flying Lotus’ “First Friday Funk” samples video game music from 1989 NES game Friday the 13th:

“Diggin in the Carts has played a small part in raising the profile of classic VGM, but lots of other things have also happened in the last five years to help that along. For instance, record labels like Data Discs and Brave Wave have done the difficult work of negotiating with rights-holders in order to release this music.”

Depending on the territory and language you’re starting from, making contact with Japanese game composers isn’t necessarily the easiest thing to do. “I'm super thankful [that we had the chance to reach out], and those relationships are ongoing. It was always intended that the documentary series was just the beginning. After meeting many of the composers, I found out that they deeply cared about the player when composing.”

There is an interesting point of difference between the Japanese composers and their UK counterparts. Dwyer muses: “In the mid-’80s, Japan was still enjoying the effects of the post-war ‘economic miracle’, also known as the ‘Bubble Era.’ These companies’ coffers were filled and so game developers [including composers] could afford to be more experimental.” This contrasts with the somewhat factory line production of games and game music coming out of the UK. “Composers like Rob Hubbard and David Whittaker were having to churn out soundtracks.

“Yes, developers at a Squaresoft or a Capcom were working in tiny cubicles, but it was a very creative environment. If you loved to make music, and you loved to play games, you probably thought you had the best job in the world working in a video game company in Japan — job security, bonuses, etc. Everyone back then seemed to be having a great time.”

Clubs of Rage

Between late 2017 and late 2018, Dwyer and team toured two complementary live VGM shows. One set featured legends Yuzo Koshiro and Motohiro Kawashima performing their music from the Streets of Rage series.

The other show was a performance of remixed game music by UK bass artist Kode9, set to visuals by the artist-animator Kōji Morimoto (Akira, Kiki’s Delivery Service, The Animatrix). Each stop on the tour featured support from DJ Dwyer himself, VJ backup from Planet Mu’s Konx-Om-Pax, and sets by notable local electronic artists who were inspired by VGM.

Of orchestral shows like Distant Worlds or Final Symphony, Dwyer comments: “They exist, they’re necessary and the producers have done incredible work to celebrate those composers and hold up those compositions as ‘real music.’

“But, for me, it’s about the intersection of electronic music and video game music. We wanted to do something that had never been done before: the composers would perform the music exactly as it was back in the day, sounding as it did through the Genesis/Mega Drive — loud, live, and amplified. We put them in the coolest, most reputable, most credible clubs and festival line-ups in the world, including Barcelona’s Sónar, London’s Fabric, and Tokyo’s Liquid Room. A particular highlight was the performance at Turin’s Club To Club.

“Our goal was to highlight how good this music was as electronic music, outside of the game. What these guys were doing is no different to what the creators of early club music were doing, be it jungle, techno, etc.; they were using rudimentary equipment and pushing it to its limits to create something new.”

“It was really well-received and I was very happy for Yuzo and Motohiro. They were rehearsing right up until the launch gig in Los Angeles, and were maybe a bit nervous [about the reception they might receive.] But we were playing in front of packed audiences 2,000-, 4,000-strong, and the energy in the room each time was amazing. They were being celebrated like rockstars.

“These composers are now aware how popular this music is [whereas they previously hadn’t necessary grasped that]; and Yuzo and Motohiro were overjoyed to have the opportunity to perform it. They spent three hours signing autographs after the Sónar festival set — I’ve never seen that in my life! It’s funny: whilst they’re chuffed about it, they’re still incredibly busy with current projects so they don’t have time to revel in it. When they returned to Japan after touring, they were back to working a million miles an hour on a million different projects.

“It's not a band playing it. It's not an orchestra playing it. It’s the original artists, and hopefully there are more to come — we’re plotting and scheming new things right now.”

Complementary compilations

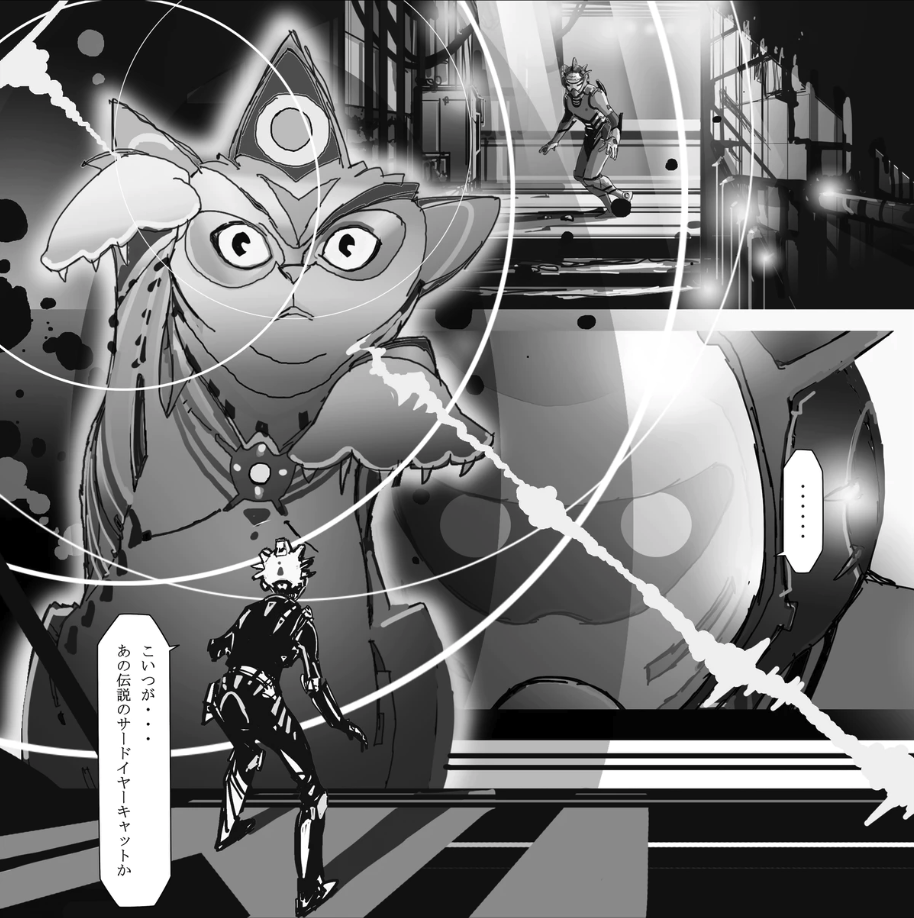

The compilation album artwork by Kōji Morimoto (left) is intertwined with the Diggin’ tie-in manga; whilst the EP artwork (right) has been adapted by Konx-on-Pax from the visuals for the live performance.

As if he needed any more to worry about, Dwyer hatched a plan with friend, music artist, and label owner Steve Goodman (aka Kode9) to release a compilation of obscure, brilliant chiptune tracks. The slightly tortuous project took two years. First, Dwyer simply had to listen through everything: “It took six months of building shortlists, getting it down from 1,000 to 500... to 34.” After that, negotiating with rights-holders “took a long, long time. It was a great experience overall though.”

The final track of the compilation — “Oblivious Past” by Kazuo Hanzawa from 1995 side-scrolling shooter Alien Soldier — is a spiritual full stop on the era of music that has so absorbed Dwyer: “It was one of the swan songs of the Genesis/Mega Drive. [Developer] Treasure were pushing the limits sonically and visually.”

More recently, Hyperdub released an EP featuring Kode9 remixes of various tracks from the original compilation.

And, naturally, Kode9, Dwyer and Kōji Morimoto co-created a manga set in Neo-Tokyo in the year 2099 to tie-in to the releases.

Beyond mining carts to diggin’ in the discs

Although Dwyer confessed to previously not being particularly enamoured with post-1995 VGM, he’s come around on the post-chiptune era. Like any researcher-historian worth their salt, he’s found it important and rewarding to delve into what came next; namely the catalogues of the so-called ‘5th Gen’ 32-bit and 64-bit consoles, as well as obscure disc-based systems like the PC-Engine CD-ROM and Fujitsu’s FM Towns.

In particular, ambient VGM has been tickling his ears — including the N64 work of Koji Kondo (e.g. The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask), and Tim Follin’s music for Ecco the Dolphin: Defender of the Future. His recent ambient mix for Adam Oko’s NTS radio show is quite sublime (jump to the 1 hour mark):

The latter series of the Diggin in the Carts radio show have also seen him interviewing contemporary composers including Richard Vreeland aka Disasterpeace (FEZ, Hyper Light Drifter).

Be sure to keep an eye out for whatever Nick Dwyer and Diggin in the Carts do next – Twitter: @NickDwyer | SoundCloud.com/diggininthecarts

If you haven’t already, check out the six-part documentary series, featuring interviews with Hideo Kojima, ‘Hip’ Tanaka, Yoko Shimomura, Yuzo Koshiro, Flying Lotus, Anamanaguchi, and many more – YouTube playlist

The radio shows are all up online:

– Series 1 on SoundCloud – our recommendation is to check out the first episode featuring an interview with Manabu Namiki, who created the Detroit-influenced score for Battle Garrega

– Series 2 is also on SoundCloud

– Series 3 – search for “diggin in the carts season 3” on www.mixcloud.com – we recommend checking out Nick’s interview with his VGM hero Ben Daglish during episode 6; also his chats with Anamanaguchi (ep 5) and Disasterpeace (ep 7)

Hyperdub releases:

Be sure to read “Nick Dwyer’s Favorite Early Japanese Video Game Soundtracks“

Also, Nick introduced Yuzo Koshiro for a talk at the Red Bull Music Academy (be sure to turn on closed captions.)